Our Bodies

Speak the Truth

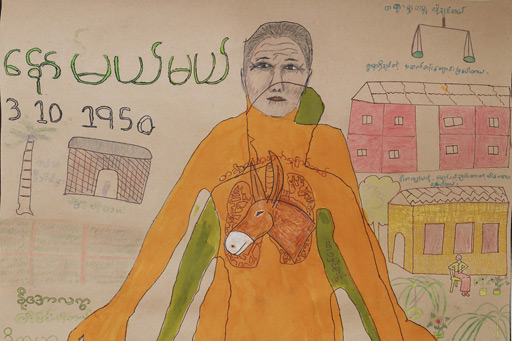

Htu Lum was born in a remote village in the mountains of Kachin State. Her father was a teacher and a farmer, and she helped to raise buffalo from an…

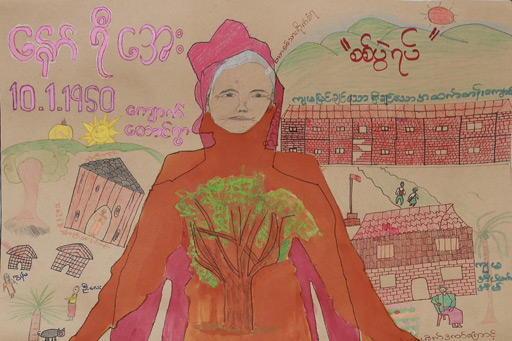

Born in a mountainous village in Kachin State with no public facilities, Ah Htoi moved to a larger town when she was 5. There she attended a school where she…

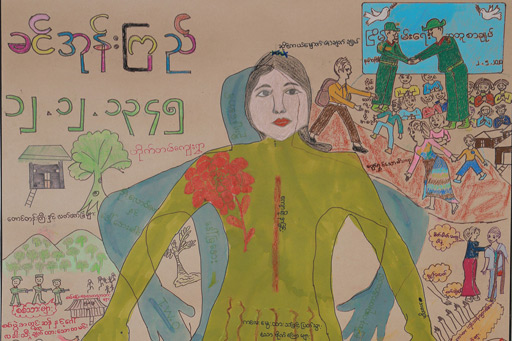

Ah Bu was born in a small village in Kachin State. Fighting occurred near the village all the time. Being the oldest girl of seven children, Ah Bu had to…

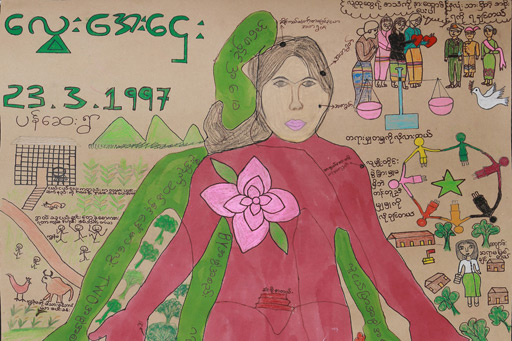

Hkawm Sam Pan grew up on her family farm in a rural portion of Kachin State. One of her happiest childhood memories is of going to festivals with her father….

Born in a small village in Karen State, Naw Mai Mai has worked hard for her family and her community for her entire life. With no schools or temples nearby,…

Naw Yi Aye grew up in a remote village in Karen State as the third of five children. She remembers happy times in her childhood singing and playing in the…

Ethnically Ta’ang, Khin Ohn Kyi’s life has been shaped by conflict-related violence and her deep religious faith. Born on a small farm and tea leaf plantation in northern Shan State,…

Ethnically Ta’ang, Lway Aye Htay began her life in a village free from conflict. The eldest of three siblings, she was in charge of cooking and carrying the water while…

An Introduction

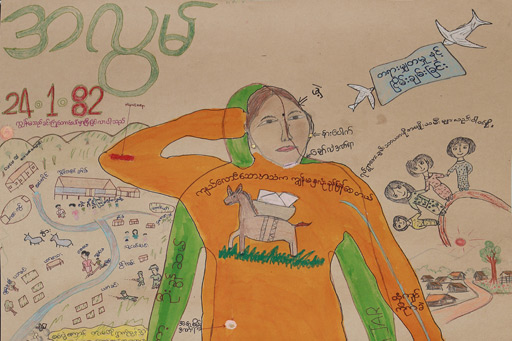

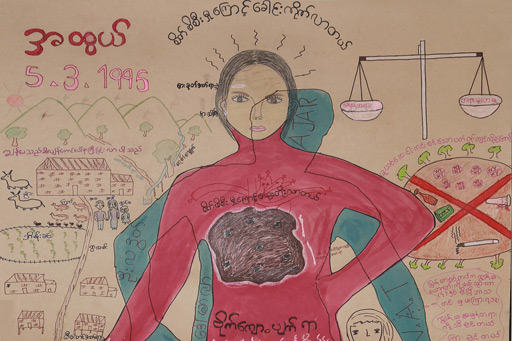

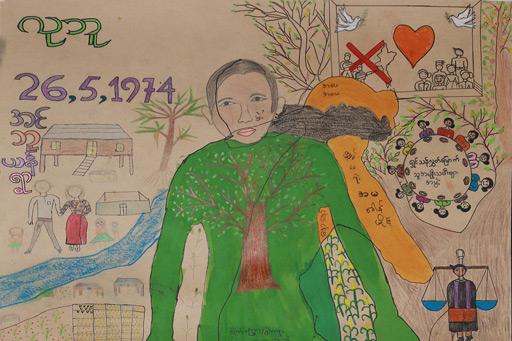

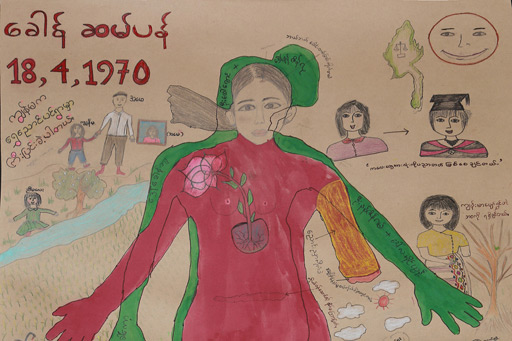

The women of Myanmar have shown strength and resilience in the face of decades of conflict, violence, and repression. This exhibition stands testament to their indelible spirit, connecting us to the stories of 12 women survivors through life-size body maps they themselves created.

In March 2020, as the Covid-19 pandemic was rapidly unfolding, Asia Justice and Rights (AJAR), Karen Women’s Organization (KWO), Kachin Women’s Association Thailand (KWAT), Ta’ang Women’s Organization (TWO) and Vimutti Women’s Organization (VWO) brought together 12 women survivors of human rights violations in the rolling hills of northern Myanmar to share their stories. The women, who ranged in age from 20s to 70s, traveled long distances to take part in an experience of truth-telling, solidarity, and creative expression.

Shirley Gunn, a South African artist, former political prisoner and underground commander, and activist, facilitated a five-day process guiding the women to reflect on the different stages of their lives and draw them onto life size posters of their bodies. Over the week, the women shared stories of sadness and loss, happiness and relief, anger and determination. They shared memories of the past and hopes and fears for the future. Few had any artistic experience; some had never picked up a crayon or paintbrush. Yet by the end of the week, they had created vibrant, colorful body maps that captured the richness of their lives.

These body maps also bear witness to the many violations that women in Myanmar have experienced: the scars and healing wounds of landmine and gunshot injuries, the chronic pain from years spent in detention, the ongoing grief for friends and family members killed in conflict or vicious attacks by the Myanmar Army.

These body maps depict the lives of women before the 1 February 2021 coup, revealing decades of abuse and violations. These body maps can help place women’s stories in context. Far from being the start of violence, the coup has been just another chapter in a long history of suffering, struggle and determination for most women.

A public exhibition in Yangon was planned for March 24, 2020. Yet sadly the Covid-19 pandemic intervened, the exhibition was postponed, and the body maps were placed in storage in the hopes that an exhibition could take place once restrictions on travel and public events were lifted.

Before this could happen, the Myanmar Army perpetrated the coup, and the body maps went into hiding. Recognising the very serious threat the maps posed to the security of the women artists, AJAR took the incredibly difficult decision to destroy the maps. We hope the day will come soon where these women survivors can come together again in person to share their stories directly to the public. In the meantime, we offer this digital exhibition. The names, faces, and some of the defining details of the body maps have been purposefully blurred to protect the identities of the survivors. The truth, however, remains.